Efficient Capital Markets?

Research, history, and applications

Dr. Jonathan Cooley 蒋能胜 DBA, MBA, BS

Abstract

This article explores the concept model of efficient markets made popular by Fama, the 2013 Nobel Prize winner in economics, and his co-winner, economist Robert Shiller. Shiller has challenged the efficient market hypothesis as a “half-truth” since the late 1990s through today concluding that although capital markets can be efficient, they can also be irrational and not properly reflect asset values. The article further explores the literature and current articles regarding those key factors that can – and do – make domestic and international public capital markets inefficient. The article concludes there are four key elements acting on efficient markets and these forces will not necessarily be mitigated through regulation, and the effect of these four forces can be extended into other capital asset markets.

Keywords: Stock Crash, Efficient Markets, Stock, Random Walk, Insider Trading, Irrational Markets, Information Velocity, Equity Markets, Arbitrage, Shanghai Exchange, Shenzen China exchange, International Accounting Standards IAS, Artificial Intelligence AI

Historical Overview

Market efficiency assumes that asset prices will adjust up or down and immediately reflect all information available to investors; therefore, investors cannot outperform the markets or other investors in a consistent manner through abnormal risk-adjusted returns. The concept was first discussed regarding the public financial markets by Charles Conant in 1904 (Conant, 1904). The term was coined by Harry Roberts of the University of Chicago, and made further famous by Eugene Fama in 1969 (Fama, Fisher, Jensen, & Roll, 1969). In 1960, the Ford Foundation funded CRSP (Center for Research in Security Prices). The resulting database allowed scholars to empirically study the actual price history of public stocks all the way back to 1926 for the first time, adjusted for splits, dividends, and the like (Shiller, 2012). This allowed a revolution in finance and first demonstrated that actual results were consistent with the efficient market hypothesis (Boettke, 2008; Lehrer, 2010).

The concept of the random walk (Malkiel, 1999; Shlller, 2012) is also central to the efficient market hypothesis; essentially, the historical price trend of a stock or stock market does not influence the next price point and prices adjust to fully reflect all publicly available information.

On the other hand, technical analysis looks to stock performance charts to predict buy and sell points based on investor performance without regard to public information. An example is the “head-and-shoulders” pattern of price changes that key buy/sell orders (Hodnett & Heng-Hsing, 2012; Shiller, 2012). This approach falls into the behavioral finance pricing hypothesis that markets reflect investors’ moods, fears, expectations, and prejudice. Shiller suggests that the markets reflect both efficiency and behavioral components.

Based on original research and following studies by Fama (1969, 1970, 1998), Higgins (2012) summarizes there are three forms of efficient markets: i) the weak-form, ii) the semi strong-form, and iii) the strong-form. Fama concluded that extensive market pricing tests indicate that most financial markets are semistrong – current prices fully reflect all publicly available information. Therefore, the markets may be efficient on the whole; however, other studies indicate they can and do become inefficient. Key underlying support for the efficient market then becomes “what information is available, to whom, and when.”

This article limits the discussion to public stock markets and explores a few key issues that may cause these markets to be inefficient. Similar arguments can, however, also be made with the pricing of other assets such as debt instruments (e.g., bonds, subordinated debt, mortgages) and commodities.

Efficient Capital Markets

Let us consider the argument that not all markets are efficient and the efficient public market hypothesis is a “half–truth” (Boettke, 2010; Shiller, 2012). Nagaswaren (2013) argues that markets are inherently inefficient in concert with the conclusions of other studies (Hodnett&Heng-Hsing, 2012; Kitson,2012; Leroy,1976). For example, to allow markets to adjust both up and down, there should be no restrictions on shorts, puts or futures. Market regulators worldwide, however, have placed certain restrictions on all these instruments, and shorts do not even exist for some markets such as the China exchanges. Bull (optimistic) and bear (pessimistic) market cycles also suggest there is a strong public clustering sentiment (even a “herd mentality) involved in asset pricing.

Current articles and the literature suggest there are primary causes for inefficient markets and these can be categorized into four areas. These are:

- Transparency: a general lack of transparency in financial reporting

- Insider Trading: information generally unavailable to public investors

- Irrational Markets: differences in asset pricing models and assumptions

- Information Velocity: the advantage/disadvantage of the speed with which some investors receive publicly available information

Transparency

When investigating the efficiencies of international capital markets, one must recognize that each country’s public market laws and policies, as well as the inclination for public information transparency and efficient distribution of such information can greatly alter market behavior (ACCA, 2013). The ACCA studied stock prices between 2003 and 2009 on both the Shanghai and Shenzen China exchanges. The study concluded that there was a direct, positive effect of improved earnings disclosures on stock prices for Chinese companies who have begun to use International Accounting Standards (IAS). The research also indicated there were five prime motivations for these companies’ adoption of IAS. These were:

- “A high level of dependence on the equity markets for funding

- Being outside of direct Government control and lacking access to Government subsidies

- Being based in a less-developed region

- Having significant foreign ownership

- Being a [exporting or global] manufacturer.”(ACCA, 2013, Abstract, p 3)

Several countries have proposed and accepted the IAS. However, America has not yet adopted these standards. American companies must comply with U.S. regulations as set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Companies whose stock trades in American exchanges must, therefore, reconcile their financial statements to FASB rules. As Higgins (2012) notes, accounting and financial reporting are as much an art as a science.

Although there appears to be a convergence of accounting and reporting standards within the markets, with differing rules and regulation enforcement, an investor may be pricing apples and oranges between international companies or on separate exchanges even in the same industry and customer markets. This speaks to the question of what information and of what quality information is generally available for efficient markets. It also opens the door for certain arbitrage opportunities.

Insider Trading

Efficient markets assume that all information is equally available to all investors. As we have seen throughout the past thirty years, market inefficiencies have been created through insider trading – trading based in information not generally available to the public (Plott, & Sunder, 1982). To name a few of the more recent examples (Wachtel, 2010):

- 1986 Ivan Boesky, Drexel, Burnham, Lambert;

- 2001 Martha Stewart, ImClone;

- 2005 Joseph Nacchio, Qwest Communications; and

- 2009, Raj Rajaratnam, Galleon Group are only a few.

According to industry professionals, such insider trading is not going away(Schaefer, 2012). History and current news attest to this fact, although continuing regulation attempts to control it and mitigate its market effects.

Irrational Markets

Research by Einhorn and Hogarth (1978), supported by other research (Goldratt, 1990), has shown that people are poor at determining correlations subjectively. Additionally, research has documented a substantial lack of ability of both experts and non-experts to draw conclusions accurately and subjectively. These studies also show that the same people have great confidence in their decisions and may not recognize their fallible judgment (Einhorn& Hogarth).

Keynes believed that markets can become irrational. This was later argued by both Federal Reserve Chairman, Alan Greenspan (Harford & Alexander, 2013) and economist Robert Shiller (2000). Greenspan said, “”How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?” (Harford & Alexander, 2013, p.1).Shiller (2000) argued that the long stock price boom from 1982 to 1995 created an over-heated, over-priced market of irrational exuberance, foreshadowing the later world-wide financial crises. This speaks more to the concepts of behavioral finance than those who hold strictly to the efficient market theory.

Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT) effectively attempts to model market inefficiencies. The concept was developed in 1976 and attempted to incorporate macro-economic risk factors into asset pricing. Early empirical studies (Reinganum,1981) suggest that linear APT models do not properly account for asset pricing differences. Many studies since then have attempted to improve on these models (e.g., Bansal&Viswanathan, 1993). Therefore, although Higgins (2012) suggests that markets are semistrong, it can be argued that irrational markets may be efficient: The market continues to respond to available information, but these markets do not necessarily reflect accurate asset values.

Information Velocity

Finally, this leads us to the question, “Assuming all public information is available to all people, does it matter when the information is received?” Given two investors in a perfectly efficient market, if Investor A receives information on January 1 and Investor B receives it on January 5, Investor A has the investment advantage. The obvious answer to the question then is, yes; but the ability to receive, process, and act on information can now exceed the ability of humans to receive and process information beyond the human limitation of 650 nanoseconds (Invest, 2012). This becomes the realm of computer algorithms.

The concept of arbitrage operates based on inefficiencies in markets, price differences in remote markets, and investors’ access to publicly available information (Bell, 2012). The speed of this access can create an opportunity for capitalizing on new information.

Automated computer data collection and algorithms have been built to i) access and digest news and information more rapidly than humanly possible, ii) make correlations across multiple markets, industries, and data, and iii) execute fast buy/sell trades. These are called “high-frequency trading” or high-speed trading (Foxman, 2013; Koba, 2013; Shecter, 2013). Apple stock, for example, trades approximately 29,000 times per second. By 2013, computer-based trading accounted for 75% of all market trades (Farrell, 2013).

Funds and traders can take advantage of the concept of price convergence or divergence to make money. For example, a fund buys a Treasury bill (T-bill) future, trading at a slight discount to the face value of the bill itself. The fund then simultaneously sells a corresponding Treasury bill. When the difference between the original T-bill’s discounted value and the future value narrows (i.e., converges) or expands (i.e., diverges), the trade creates an arbitrage profit opportunity. Using debt leverage combined with the fund’s equity, the leveraged equity converts a small stock profit into a significant profit to equity by trading thousands of shares at a time. es 1 and 2 illustrate how the market can be affected when hundreds of these programs are running in the market.

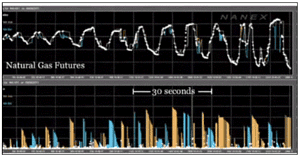

In Figure 1, notice the rapid frequency shifting of the price of a commodity, natural gas. With a consistent supply of natural gas and a world market, this commodity market should be highly efficient; however, HFT (High-Frequency Trading) can cause increased volatility in a stock price, as noted. Of importance is to note the rapid time frame for this price oscillation…hundreds of trades in milliseconds.

Figure 1. Price Fluctuation of Natural Gas Futures due to High Frequency Trading

Invest (2012). High Frequency Trading Explained. Conference proceedings.Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAGaReF9LaI. Copy for educational purposes only.

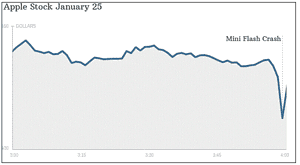

Figure 2 indicates what happens when multiple algorithms collide. In this example, Apple stock fell rapidly for a short period. These “flash crashes” apparently occur many times a day with many stocks

due to HFT and is no longer unusual in the market, happening dozens of times a day and argued that given perfect information, price differentials should cancel out such disparate market advantages. This addresses the issue of access to information and the ability to act on that information before the rest of the market. I propose that information and trading velocity then create an unfair advantage, but no more than enjoyed by John Maynard Keynes when he built his arbitrage fortune via access to faster newsprint information on the London and Paris exchanges

Figure 2: Apple Stock’s Flash Crash, January 25, 2013.

Farrell, M. (2013). Mini flash crashes: A dozen a day. CNN Money.Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2013/03/20/investing/mini-flash-crash/.Copy for educational purposes only.

Summary Conclusion

Both the literature and the continuing discourse among economists and market watchers agree that markets can become or are inefficient for several reasons. We have explored a few key reasons. The efficient market hypothesis assumes a somewhat Utopian perfection which cannot and does not exist in today’s public market – and there doesn’t seem to be a leveling change in the future. The introduction of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in computerized trading will further exacerbate these issues.

Much of the market dynamics in the past few years have not been reported yet in scholarly journals. As a result, current public articles have been used in this discussion to supplement the literature and investigate market trends. Time will allow a sufficient collection of data and research to address these in the future. It is an area ripe for additional research; however, the sheer velocity of technology may make it difficult to substantively research the cutting edge of public asset market changes.

References

AACA (2013).IFRS in China.The Global Body foyou Professional Accountants. Retrieved from http://www.accaglobal.com/en/research-insights/corporate-reporting/ifrs-china.html

Bansal, R., &Viswanathan, S. S. (1993). No Arbitrage and Arbitrage Pricing: A New Approach. Journal of Finance, 48(4), 1231-1262.

Bell, H. (2012). Velocity of Information in Efficient Markets: A Theory of Market Value Change. Journal of Investing,21(3), 55-59.

Boettke, P. (2010). What Happened to “Efficient Markets”?. Independent Review, 14(3), 363-375.

Commercial Finance Group (n.d.), Arbitrage. Retrieved from http://www.fcscfg.com/terminology/A-terms/arbitrage.htm.

Conant, C. A. (1904). Wall Street and the Country. Houghton, Mifflin & Company.

Einhorn, H. & Hogarth, R. (1978).Confidence in judgment: Persistence of the illusion of validity.Psychological Review, Vol 85(5), Sep 1978, 395-416. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.395. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/rev/85/5/395/

Fama, E., Fisher, L., Jensen, M., & Roll, R. (1969).The adjustment of stock prices to new information. International economic review, 10.

Fama, E.F. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. Journal of Finance 25(2), 383-417.

Fama, E. (1991). Efficient capital markets II. Journal of Finance, 46(5), 1575–1617.

Fama, E. F. (1998). Market efficiency, long-term returns, and behavioral finance.Journal of Financial Economics, 49(3), 283–306.

Farrell, M. (2013). Mini flash crashes: A dozen a day. CNN Money. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2013/03/20/investing/mini-flash-crash/

Foxman, S. (2013).High-frequency trading is bad for normal investors, researchers say. Quartz.June 18. Retrieved from http://qz.com/95088/high-frequency-trading-is-bad-for-normal-investors-researchers-say/

Goldratt, E. (1990)TheHaystack Syndrome: Sifting Information Out of the Data Ocean. North River Press Publishing, Great Barrington, MA, 1990. ISBN 0-88427-184-6

Harford, T. & Alexander, R. (2013). Are markets ‘efficient’ or irrational? BBC News Magazine. October 2013. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-24579616.

Hodnett, K., &Heng-Hsing, H. (2012). Capital Market Theories: Market efficiency versus investor prospects. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 11(8), 849-862.

Invest, n.a. (2012). High Frequency Trading Explained. Conference proceedings.Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAGaReF9LaI.

Kitson, M. A. (2012). Controversial orthodoxy: The efficient capital markets hypothesis and loss causation. Fordham Journal Of Corporate & Financial Law, 18(1), 191-231.

Koba, M. (2013). High Frequency Trading: CNBC explainsCNBC. 24 Jan. Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/id/100405633

Lehrer, J. (2010). The Truth Wears Off: Is there something wrong with the scientific method?New Yorker, Dec. 13. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/12/13/101213fa_fact_lehrer

Leroy, S. (1976). Efficient Capital Markets: Comment. Journal Of Finance, 31(1), 139-141.

Malkiel, B. G. (2003). The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 59-82.

Malkiel, B. G. (1999). A random walk down Wall Street: including a life-cycle guide to personal investing. WW Norton & Company.

Mattoli, C. (2008). What is Arbitrage? White Paper: Red Hill Capital Corp.

Nageswaran, V.A. (2013). The efficient markets fad.Wall Street Journal, Mon., Oct 21, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/Opinion/p38RxhhmtARQ95mHrqdmlL/The-efficient-markets-fad.html

Plott, C. R., & Sunder, S. (1982). Efficiency of Experimental Security Markets with Insider Information: An Application of Rational-Expectations Models. Journal Of Political Economy, 90(4), 663-698.

Reinganum, M. (1981). The Arbitrage Pricing Theory: Some Empirical Results. Journal Of Finance, 36(2), 313-321.

Schaefer, S. (2012).Insider Trading Scandals Aren’t Going Away, Lawyers Say. Forbes Online.Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/steveschaefer/2012/12/06/insider-trading-scandals-arent-going-away-lawyers-say/

Shecter, B. (2013) High-frequency traders: Market friend or foe?Financial Post.Retrieved from http://business.financialpost.com/2013/10/11/high-frequency-traders-market-friend-or-foe/

Shiller, R. (2012).Efficient Markets. Retrieved from http://oyc.yale.edu/economics/econ-252-11/lecture-7

Shiller, R. (2003).From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance. Journal of Economics Perspectives, 17, 83-104

Wachtel, K. (2010). The 11 Most Shocking Insider Trading Scandals Of The Past 25 Years. Business Insider.Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/worst-insider-trading-scandals-2011-11?op=1

Hey, Jack here. I’m hooked on your website’s content – it’s informative, engaging, and always up-to-date. Thanks for setting the bar high!

Thanks Jack! I tend to overwrite and over research topics I’m interested, but glad you find it informative 🙂

My brother suggested I might like this website He was totally right This post actually made my day You cannt imagine just how much time I had spent for this information Thanks

Thanks! I hope your brother keeps reading, too. Follow my blogs and you’ll find lots of additional sources to do deep dives into things that interest you.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your blog is a breath of fresh air in the often stagnant world of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with us.

Muchas gracias. ?Como puedo iniciar sesion?

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/ro/register-person?ref=V3MG69RO

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

“Thanks for sharing such valuable information!”

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

4kql3w

25dnfv

Excellent web site. Lots of useful information here. I’m sending it to some friends ans additionally sharing in delicious. And certainly, thanks for your effort!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://www.binance.com/join?ref=P9L9FQKY

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks! https://accounts.binance.com/en-IN/register?ref=UM6SMJM3

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

d3crr7

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

yf55yx

nmuvm6

ru36k3

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

0hrk0v

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Great! Thank you so much for sharing this. Visit my websitee: free stresser

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

mbbhiq

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

ku5sly

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

sfj729

2pqfkd

Aw, this was a very nice post. In concept I wish to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and precise effort to make a very good article… but what can I say… I procrastinate alot and not at all seem to get one thing done.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

uh69an

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

00npf2

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

https://lioleo.edu.vn/dang-ky-form/4.png.php?id=miya-bet-88

https://api.lioleo.edu.vn/public/images/course/4.png.php?id=bet-spaceman

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

My web blog – https://cryptolake.online/crypto2

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Veq THGqNwNe hJmbPKW ExR lcu psDUtSZ

Hey! Quick question that’s completely off topic. Do you know how to make your site mobile friendly? My site looks weird when viewing from my iphone. I’m trying to find a theme or plugin that might be able to resolve this problem. If you have any recommendations, please share. Cheers!

usY HAQa opmdma qsxLjZte

6hbe3j

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

oaPC exkgRhnL jSUckFpS Imz tky

I am extremely inspired along with your writing abilities and also with the structure on your blog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it your self? Anyway stay up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to peer a nice weblog like this one today!

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I’ll definitely try this out.

You explained this very clearly.

With havin so much content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright infringement? My blog has a lot of unique content I’ve either created myself or outsourced but it appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my agreement. Do you know any techniques to help prevent content from being stolen? I’d definitely appreciate it.

e95vym

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

getp4j

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

igom3c

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://accounts.binance.com/zh-CN/register?ref=VDVEQ78S

bfhr2d

Your writing is not only informative but also incredibly inspiring. You have a knack for sparking curiosity and encouraging critical thinking. Thank you for being such a positive influence!

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!